How To Create Array In Assembly Language

Arrays, Address Arithmetic, and Strings

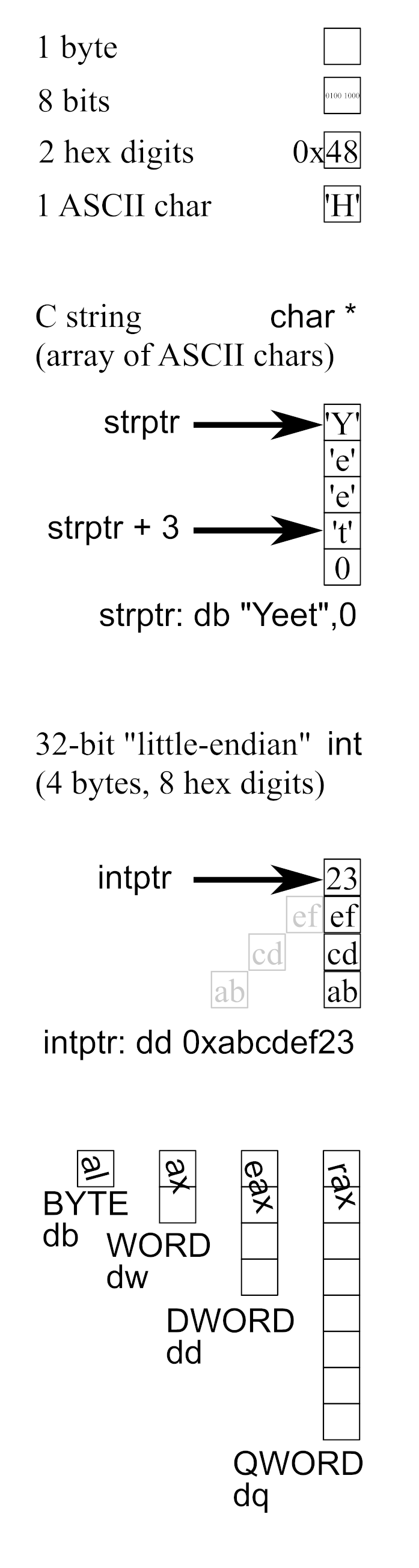

CS 301: Assembly Language Programming Lecture, Dr. LawlorIn both C or assembly, you can allocate and access memory in several different sizes:

| C/C++ datatype | Bits | Bytes | Register | Access memory | Allocate memory |

| char | 8 | 1 | al | BYTE [ptr] | db |

| short | 16 | 2 | ax | WORD [ptr] | dw |

| int | 32 | 4 | eax | DWORD [ptr] | dd |

| long | 64 | 8 | rax | QWORD [ptr] | dq |

For example, we can put full 64-bit numbers into memory using "dq" (Data Quad-word), and then read them back out with QWORD[yourLabel].

We can put individual bytes into memory using "db" (Data Byte), and then read them back with BYTE[yourLabel].

C Strings in Assembly

In plain C, you can put a string on the screen with the standard C library "puts" function:

puts("Yo!"); (Try this in NetRun now!)

You can expand this out a bit, by declaring a string variable. In C, strings are stored as (constant) character pointers, or "const char *":

const char *theString="Yo!"; puts(theString);

(Try this in NetRun now!)

Internally, the compiler does two things:

- Allocates memory for the string, and initializes the memory to 'Y', 'o', '!', and a special zero byte called a nul terminator that marks the end of the string.

- Points theString to this allocated memory.

In assembly, these are separate steps:

- Allocate memory with thedb(Data Byte) pseudo instruction, and store characters there, like db `Yo!`,0

- Unlike C++, you can declare a string using any of the three quotes: "doublequotes", 'singlequotes', or `backticks` (backtick is on your keyboard beneath tilde ~)

- However, newlines like \n ONLY work inside backticks, an odd peculiarity of the assembler we use (nasm).

- Note we manually added ,0 after the string to insert a zero byte to terminate the string.

- If you forget to terminate the string, puts can print neat garbage after the string until it hits a 0.

- Point at this memory using a jump label, just like we were going to jmp to the string.

Here's an example:

mov rdi, theString ; rdi points to our string extern puts ; declare the function call puts ; call it ret theString: ; label, just like for jumping db `Yo!`,0 ; data bytes for string (don't forget nul!)

(Try this in NetRun now!)

In assembly, there's no syntax difference between:- a label designed for a jump instruction (a block of code)

- a label designed for a call instruction (a function ending in ret)

- a label designed as a string pointer (a nul-terminated string)

- a label designed as a data pointer (allocated with dq)

- or many other uses--it's just a pointer!

We can also change the pointer, to move down the string. Since each char is one byte, moving by 4 bytes moves by 4 chars here, printing "o assembly":

mov rdi, theString ; rdi points to our string

add rdi,4 ; move down the string by 4 chars

extern puts ; declare the function call puts ; call it ret theString: ; label, just like for jumping db `Hello assembly`,0 ; data bytes for string

(Try this in NetRun now!)

Address Arithmetic

If you allocate more than one constant with dq, they appear at larger addresses. (Recall that this is backwards from the stack, which pushes each additional item at an ever-smaller address.) So this reads the 5, like you'd expect:

dos_equis: dq 5 ; writes this constant into a "Data Qword" (8 byte block) dq 13 ; writes another constant, at [dos_equis+8] (bytes) foo: mov rax, [dos_equis] ; read memory at this label ret

(Try this in NetRun now!)

Adding 8 bytes (the size of a dq, 8-byte / 64-bit QWORD) from the first constant puts us directly on top of the second constant, 13:

dos_equis: dq 5 ; writes this constant into a "Data Qword" (8 byte block) dq 13 ; writes another constant, at [dos_equis+8] (bytes) foo: mov rax, [dos_equis+8] ; read memory at this label, plus 8 bytes ret

(Try this in NetRun now!)

Accessing an Array

An "array" is just a sequence of values stored in ascending order in memory. If we listed our data with "dq", they show up in memory in that order, so we can do pointer arithmetic to pick out the value we want. This returns 7:

mov rcx,my_arr ; rcx == address of the array

mov rax,QWORD [rcx+1*8] ; load element 1 of array

retmy_arr:

dq 4 ; array element 0, stored at [my_arr]

dq 7 ; array element 1, stored at [my_arr+8]

dq 9 ; array element 2, stored at [my_arr+16]

(Try this in NetRun now!)

Did you ever wonder why the first array element is [0]? It's because it's zero bytes from the start of the pointer!Keep in mind that each array element above is a "dq" or an 8-byte long, so I move down by 8 bytes during indexing, and I load into the 64-bit "rax".

If the array is of 4-byte integers, we'd

declare them with "dd" (data DWORD), move down by 4 bytes per int array element, and store the answer in a 32-bit register like "eax". But the pointer register is always 64 bits!mov rcx,my_arr ; rcx == address of the array

mov eax,DWORD [rcx+1*4] ; load element 1 of array

retmy_arr:

dd 0xaaabbbcc ; array element 0, stored at [my_arr]

dd 0xc001007 ; array element 1, stored at [my_arr+4]

(Try this in NetRun now!)

It's extremely easy to have a mismatch between one or the other of these values. For example, if I declare values with dw (2 byte shorts), but load them into eax (4 bytes), I'll have loaded two values into one register. So this code returns 0xbeefaabb, which is two 16-bit values combined into one 32-bit register:mov rcx,my_arr ; rcx == address of the array

mov eax,[rcx] ; load element 0 of array (OOPS! 32-bit load!)

retmy_arr:

dw 0xaabb ; array element 0, stored at [my_arr]

dw 0xbeef ; array element 1, stored at [my_arr+2]

(Try this in NetRun now!)

You can reduce the likelihood of this type of error by adding explicit memory size specifier, like "WORD" below. That makes this a compile error ("error: mismatch in operand sizes") instead of returning the wrong value at runtime.mov rcx,my_arr ; rcx == address of the array

mov eax, WORD [rcx] ; load element 0 of array (OOPS! 32-bit load!)

retmy_arr:

dw 0xaabb ; array element 0, stored at [my_arr]

dw 0xbeef ; array element 1, stored at [my_arr+2]

(Try this in NetRun now!)

(If we really wanted to load a 16-bit value into a 32-bit register, we could use "movzx" (unsigned) or "movsx" (signed) instead of a plain "mov".)| C++ | Bits | Bytes | Assembly Create | Assembly Read | Example |

| char | 8 | 1 | db (data byte) | mov al, BYTE[rcx+i*1] | (Try this in NetRun now!) |

| short | 16 | 2 | dw (data WORD) | mov ax, WORD [rcx+i*2] | (Try this in NetRun now!) |

| int | 32 | 4 | dd (data DWORD) | mov eax, DWORD [rcx+i*4] | (Try this in NetRun now!) |

| long | 64 | 8 | dq (data QWORD) | mov rax, QWORD [rcx+i*8] | (Try this in NetRun now!) |

| Human | C++ | Assembly |

| Declare a long integer. | long y; | rdx (nothing to declare, just use a register) |

| Copy one long integer to another. | y=x; | mov rdx,rax |

| Declare a pointer to an long. | long *p; | rax (nothing to declare, use any 64-bit register) |

| Dereference (look up) the long. | y=*p; | mov rdx,QWORD [rax] |

| Find the address of a long. | p=&y; | mov rax,place_you_stored_Y |

| Access an array (easy way) | y=p[2]; | (sorry, no easy way exists!) |

| Access an array (hard way) | p=p+2; y=*p; | add rax,2*8; (move forward by two 8 byte longs) mov rdx, QWORD [rax] ; (grab that long) |

| Access an array (too clever) | y=*(p+2) | mov rdx, QWORD [rax+2*8]; (yes, that actually works!) |

Loading from the wrong place, or loading the wrong amount of data, is an INCREDIBLY COMMON problem when using pointers, in any language. You WILL make this mistake at some point over the course of the semester, and this results in a crash (rare) or the wrong data (most often some strange shifted & spliced integer), so be careful!

Walking Pointers Down Arrays

There's a classic terse C idiom for iterating through a string, by incrementing a char * to walk down through the bytes until you hit the zero byte at the end: while (*p++!=0) { /* do something to *p */ } If you unpack this a bit, you find:

- p points to the first char in the string.

- *p is the first char in the string.

- p++ adds 1 to the pointer, moving to the next char in the string.

- *p++ extracts the first char, and moves the pointer down.

- *p++!=0 checks if the first char is zero (the end of the string), and moves the pointer down

Here's a typical example, in C:

char s[]="string"; // declare a string char *p=s; // point to the start while (*p++!=0) if (*p=='i') *p='a'; // replace i with a puts(s);

(Try this in NetRun now!)

Here's a similar pointer-walking trick, in assembly:

mov rdi,stringStart again: add rdi,1 ; move pointer down the string cmp BYTE[rdi],'a' ; did we hit the letter 'a'? jne again ; if not, keep looking extern puts call puts ret stringStart: db 'this is a great string',0

(Try this in NetRun now!)

(We'll see how to declare modifiable strings later.)How To Create Array In Assembly Language

Source: https://www.cs.uaf.edu/2017/fall/cs301/lecture/09_15_strings_arrays.html

Posted by: montgomerycourer1950.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Create Array In Assembly Language"

Post a Comment